Once upon a time the streets of London were very smelly indeed.

This is not surprising, because proper sewerage systems were not introduced there for years after those clever Romans left.

Cesspits were de rigeur for a very long time, until in 1815 a basic sewerage system carried a lot of London’s waste into the Thames. A solution so simple, it ought to have been elegant.

And it would have been, were it not for the great water wheels. These had sat at London Bridge since 1582, fetching water from the Thames towards the streets and houses of the good people of London.

And so, when house waste was permitted to be carried to the Thames in the existing sewers, a particularly malignant water cycle ensued.

Some really very advanced bacteria cultures would be expelled from the good London folk, transported down to the Thames, and then piped back up to them via the miracle of antiquated waterwheel.

They drank. They cooked. They bathed.

And all the time, Mme. Cholera waited in the wings.

In those days, London had 200,000 cesspits, and emptying a cesspit cost a shilling. One rarely had the money to pay up: and there it sat.

When the crisis reached its climax London could think of no elegant words in which to couch the pungent atmosphere of the big city.

They simply called it The Big Stink.

It is always gratifying when those who make the decisions are finally laid low, despite their privileged backgrounds and lifestyles.

It came to pass that the capital little riverside location for the Houses of Parliament rendered the decision makers a little too close to the aforementioned pungency for comfort.

Indeed, it became rather too smelly to think.

And so, of course they dipped into the country’s voluminous pockets and equipped the city with a system which not only rid them of the smell, but sent that scarlet woman Mme Cholera- why I have cast her as French I have no idea- packing, too.

These days our system is not purdy, but she sure shifts the dirt. The only things most of us smell as we walk her streets are exhaust fumes and hot-dog stands.

I must reverse and rewind a little to a remedy for London’s smells which was fit for a queen.

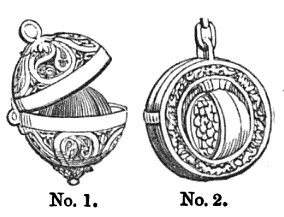

Pomanders were really popular from mediaeval times to the seventeenth century. They were intended to be protection against pestilence: useful in times of plague: and to ward off the smells which would insist upon intruding upon one’s day to day life in the metropolis.

They could be made of silver or gold, and were usually stuffed with aromatic herbs. A nineteenth century account claims to have found a recipe for a pomander used by Henry VII’s daughter Mary.

According to Privy purse expenses of the Princess Mary, daughter of King Henry the Eighth, afterwards Queen Mary, the ingredients were storax, calamite, labdanum and benzoin resin.

Two purposes for those pomanders: to ward off smells; and fight disease. That ancient concept of a miasma will keep popping up: bad air can make us unwell, in both body and spirit, according to physicians from the Middle Ages onwards.

I love the title of a book from the seventeenth century, written by philosopher of the day, Robert Boyle. It’s called ‘Suspicions about the Hidden Realities of the Air”. He voices his uneasy hunch that air is so much more than the empty nothingness it was thought to be at the time.

We know so much these days about bacteria, and microorganisms. And of course they can be airborne.

But this feeling that there is more in heaven and earth than is dreamt of in our philosophy: that the humours are still alive and well and must remain in balance: that we have suspicions about hidden realities: what a seductive set of suspicions these are.

Once I picked up a big fat book in a bookshop and I read the blurb. The author was Robertson Davies, that Canadian author who writes with such scholarly insight and compassion about things we may not yet have dreamt of in our philosophy.

The book landed like a meteor and my life has never been quite the same since. I feel a re-reading coming on.

It was called The Cunning Man, and it was the collected reflections of Dr Jonathan Hullah. He is a doctor, trained thoroughly in western medicine, but whose early experiences of Native American medicine have a lasting effect on the way he treats the whole person.

I have always adored Davies’s writing. He has such scholarly, gentle ways, and each of his characters, in each of his books, is beautufully painted. His greatest strength is the way he brings matters metaphysical into comparatively contemporary life. His world view is complex, using the lessons of the past to tread softly towards questions for the future.

He gestures, with infinite courtesy, towards hidden realities.

Is it too impish to borrow from Davies, and compare those little pomanders to something else?

There is a little piece of slang which appeals to me.

The word ‘mojo’ is immortalised, of course, by that pastiche of British spyhood, Austin Powers.

But it goes back much further than Austin, whose sense of humour renders him irresistible to me.

It comes from somewhere far from us in Britain. Thought to originate in Africa, the mojo was a small bag of herbs, sometimes including other objects thought to be powerful, like a coin.

It was worn close to the body. And it was thought to have supernatural powers. It could bring good luck, or protect one from evil.

Rather than warding off disease, the mojo warded off misfortune.

These days, the word has relaxed, smoked a joint or two, and sprawled out into meaning: the essence of one, one’s personal magnetism and charm. If one’s mojo is with one, one has one’s wellbeing. One is all one could be.

For thousands of years we have grappled with how to achieve our own wellbeing. Even today we are continuing to research and learn. And I am thankful for the advances which have saved my life on more than one occasion.

But I love to peer down the centuries, and read the old theories.

Because man makes sense of his world, not only through story, but through the theories he propounds, in any age.

And like a great-granddaughter, rummaging through a hope chest, I root around in case there might be something forgotten inside, which could be of use today.

If only metaphysically.

Metaphysically might be the most important way.

I plowed through a stack of Davies’ novels in the 90s, but not The Cunning Man. That’s two you’ve added to my list today. No, three. Thanks much.

Such a lovely compassionate read. I’ve persuaded myself, tonight, to re-read lots of his stuff.

Reading lists are very long things……I’ve only just started War and Peace for the first time, so Davies will have to wait awhile:-)

I think maybe i have temporarily lost my Mojo.

Has anyone seen it?

I did today. I think it’s the UK in November. It’s what inspired the post.

Hope you find yours soon…

Sam Pepys famously had a bit of trouble with the lack of a proper disposal system:

” going down into my cellar … I put my foot into a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr Turner’s house of office is full and comes into my cellar, which doth trouble me; …”

October 20th 1660

Hi Jan, good to have you front of house for a change! The Pepys quote is priceless. I shall learn it by heart.

Another wonderful piece, Kate, and I like the new format.

Thanks Penny:-) Tinkering around with it now.

I just remembered a porcelain pomander I was given by my grandma, wherever could it be?

Must have run off on a little holiday with my own mojo …

How lovely! Pomanders are the sort of objects I would like to collect. Very covetable. Hope you find it, and the mojo, soon…

I like the new format of your blog… but at the moment just to the right of the little piece where you invite us in to have a chat there is a greyed out area which looks as if it would be fine place for another photo… is that possible?

Yup, its a glitch in the theme, Pseu,I’m waiting for WordPress to tell me how they’ve fixed it. Its meant to feature the day’s picture…

Aha!