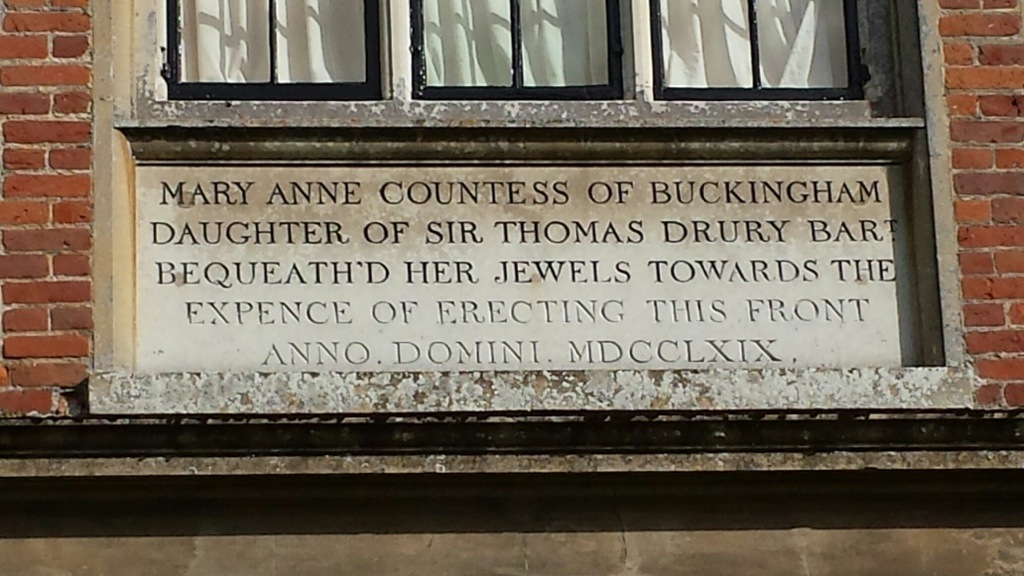

Mary Ann Drury.

This fresh young face stares down from the wall of the Chinese dressing room at a fairytale-towered mansion buried deep in the countryside of North Norfolk: Blickling Hall. She set a puzzle for passers by in 1769, and they have been puzzling ever since.

Almost nothing is a certain as death, and Mary Ann died in 1769, aged just 29. She had been born with a substantial fortune of £50,000, and her wealth would have been subsumed into the Hobart dynasty, the Earls of Buckingham, without trace, had this memorial not been erected in her honour.

The West Wing of Blickling Hall is magnificent. A Jacobean building, it was revamped to reflect Georgian tastes, with a classical feel. And it was all made possible by a bequest in a will.

What I have managed to dig up is a series of fragments of other stories which have a bearing on this one.

The first fragment is the portrait of Mary Ann herself. It was painted in 1754, when she was 14, and what I have shown you is only a detail. The whole painting looks like this:

She is sitting with her mother, Martha, Lady Drury. And her sister Jocosa is noticeably absent. We don’t know why; some theorise that it has been trimmed to cut out her sister at some point in its life.

Just saying.

The second fragment is the story of her death. No one can seem to tell me why she died but everyone seems to assume that childbirth took its toll on that slight frame. She had three daughters, no sons; and I cannot trace the birthday of the youngest, Lady Caroline, who lived until 1850. But it is said that Mary Anne was taken ill in the gorgeous parkland surrounding Blickling; and that they bundled her into a sedan chair to get her back to the house.

But she never made it. She died in the chair, being carried across the gardens of Blickling towards the towers of the house. She was buried in a pyramid-shaped mausoleum alongside her husband and his second wife.

It seemed to me such a singular thing, to put up a plaque commemorating the use of the jewels for the renovation of the West front. The action of a most singular mind.

This is Henrietta Howard. A captivating woman (and reputedly mistress of George II) in her late teens her father, creator of the present Blickling, was killed in a duel on the Holt to Norwich road, and thus a dynasty could have crumbled along with Blickling Hall, were it not for the intelligence and tenacity of Henrietta. She knew poverty and hunger. She married, unhappily, the waistrel younger brother of the Earl of Suffolk, but sold her long brown hair to escape the poverty the marriage brought the couple, and buy passage to Hanover; where there was an ageing German prince with prospects. He was to become George I.

She cultivated acquaintance with the prince’s family and was made his secretary, returning to England when George I took the throne.

Later, she became Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Caroline. It seems George II was a bad-tempered curmudgeon and Harriet shielded her Queen from the worst of his excesses. Harriet used her influence to have her brother created first Earl of Buckingham. The king’s ministers saw Henrietta as an intellectual equal: she was a great friend of artists and intellectuals inclufing Alexander Pope. But Pope said of her that she had an “‘air of sadness about her’, ‘not loving herself so well as she does her friends’.

She was highly respected by the second Earl of Buckingham, Mary Anne’s husband. He consulted her and listened to her on the detail of managing and renovating Blickling.

It’s my opinion that the other woman behind Mary Anne’s plaque was Henrietta.

Your thoughts?

If you want to read the full story of Henrietta, read Lucy Worseley’s excellent article in the Daily Mail here. There is, finally, a happy ending to her story.

Good on Henrietta if it was her doing. Love the detail in the clothing in both paintings.

Henrietta’s is a masquerade outfit, Cindy. She was kown for her impeccable taste in clothes. I covet that dress.

Henrietta certainly went through the mill to get to where she did. Again, a story one would expect to find in a romantic novel rather than in a historical account.

It does seem more than likely that her stamp is on that addition. She seems to have become good at putting on brave fronts.

I agree totally, Col. Someone who stands up for the downtrodden; though not always for herself..

Most surprising to me . . . that no one is wearing jewels in their portraits. If not then, when?

That is interesting, Nancy. Maybe less was seen as more on these occasions?

Reblogged this on Luxury and Queen's.

Many thanks!

You are very welcome!!!!!!! 🙂

I think this theory has merit, Kate. It makes sense to me that a woman would consider this detail.

Quite possbly. Though, of course, we shall never know…

I read Lucy Worseley’s story about Henrietta and I’m baffled Kate. What happy ending was there for Henrietta? Okay, at age 46 she finally married a guy she loved, but she was a widow eleven years later. She died in poverty around age 78 in 1767 — two years before Mary Ann bought her rainbow in 1769 at age 29. Maybe I’m just a fog-headed Yank, but I cannot connect the dots between these two.

To me, Virginia, the tragedy of Henrietta’s life was that from the moment her father was killed in a duel, despite her considerable intelligence and gifts, she was forced to react to events others caused. She was not in control of her life. , ‘I have been a slave 20 years without ever receiving a reason for any one thing I ever was oblig’d to do’, Worseley quotes her as saying.

For me, the happy endng was inheritance and freedom from the Royal Court, not necessarily finding someone she loved. Finally, she was in control, and had a chance for engineering happiness in life. Her final penury was her own making, and penury for an aristocrat with relations who lived at Blickling would not have been the poverty of the peasants down the road. She died at a ripe old age and left behind a formidable reputation.

As for dying two years before Mary Ann, it is documented that her opinion was highly valued at Blickling in all matters to do with the house and estate. There would have been ample time for the two women to develop a relationship, and wills are written well in advance and filed carefully away; and the Duke could well have discussed the matter with his aunt, and suggestions made, years before Mary Ann died.

So it’s possible. Probable might be pushing it a little.

Interesting speculation Kate. How unfortunate that we cannot time travel to learn what really did happen.

I’m sure if you think it is possible, then it is indeed possible 😉 She seems very creative in her face with adversity – a woman to be admired.

Versatile indeed, Gabrielle 🙂

I love these historical posts Kate 🙂

They are wonderful to research, Tandy.

So much tragedy accompanying these lives. I know people didn’t often see middle age, but even their younger years were so marred by loss. Yet we look at their portraits and their houses, and think about their jewels, and really do want to know that their lives mattered. Somehow this story really touched me! I would like to think Henrietta was behind the plaque. It somehow seems fitting.

John Hobart and Mary Ann (Drury) Hobart actually had four daughters (only three lived to adulthood). The youngest, :Lady Julia Hobart was born December 17, 1769 and died May 3, 1771. She is also buried in the mausoleum at Blickling. Mary Ann died December 29, 1769 (12 days after Julia was born). It seems a wonder that Mary Ann was out and about in the parkland when considering childbirth was much more difficult and recovery time took longer in those days. I had not heard this story of the parkland before now and always figured she died from complications to do with childbirth. It sounds sinister but she had not produced a male heir and only nine months after Mary Ann’s death, John remarried to Caroline Conolly. If the sale of Mary Ann’s jewels came before John’s Aunt Henrietta aka Harriet Howard’s death (his father John’s sister), then this theory of her involvement might be a possibility or even probability although it seems more likely they were sold after her death and two years after Harriet’s.

However, as an interesting aside: John Hobart was ambassador to Russia 1762-65 (during Mary Ann’s life). His 2nd wife Caroline willed her emerald necklace to her daughter Amelia. Amelia died childless and willed the necklace to her nephew John William Robert Kerr (son of Harriet Hobart, one of Mary Ann’s daughters). Interesting that she didn’t bequeath it to one of her three full-blooded brothers’ children. The Kerr’s have always had the understanding that the emerald necklace was gifted to John by Catherine the Great (Google Catherine the Great Emerald Necklace). So, it looks to me as if the necklace was given to him intended for Mary Ann, his wife. Was this necklace and earrings the “jewellery” that paid for the wing renovations by being John’s wedding gift to Caroline that brought her income into the estate as actual funds? Perhaps the plaque was some sort of guilt offering? Could all of this be why Amelia put the necklace back with the descendants of the woman they were meant to be with in the first place???

Such a curious web of goings-on these aristocrats weave!